First of all, it's an incredible show. The Cultural Center never looked so good. As Margaret [McCurrey] said last night, this is a much better venue than in Venice. I really am thrilled by the exhibition, by the energy of the catalog, the series of events that are going on and on and on for the next many weeks. This show that emanates from Chicago is the beginning of a rebirth in a certain way of the energy that we have lost as architects in this city until now.

So said 85-year-old godfather of Chicago architecture Stanley Tigerman of the opening day of the first Chicago Architecture Biennial, a massively ambitious exhibition of the work and thought of over one hundred invited designers from more than 30 countries. The theme of the Biennial, The State of the Art of Architecture, is actually crib of a 1977 conference organized by Tigerman as a shot-across-the-bow of the perceived icy grip of the followers of Mies van der Rohe on architectural practice and discourse.

In his generally upbeat review of the Biennial, Chicago Tribune architecture Blair Kamin called the range of work "uneven", with a "lack of thematic coherence that could have benefited from "a stronger curatorial hand."

To which I can only reply, "Praise God." The last thing architecture in Chicago - or anywhere - needs right now is a curator's heavy thumb pre-digesting whose ideas are admissible, or straight-jacketing the anarchic world of contemporary architecture into a neat little box.

The strength of the Chicago Architecture Biennial is its catholicity. Rightfully, co-curators Sarah Herda, Director of the Graham Foundation, and architect and author Joseph Grima did their due diligence of ensuring participants were at a high level of accomplishment, and then largely got out of the way. Much like a Mahler Symphony is said to encompass the world, the first Chicago Architecture Biennial offers up the experience of encountering a universe of architecture, with all of its differences in outlook, technique and philosophy. Some of it will astonish, some annoy, some appall. But Herda and Grima attempt to give us the thing whole. Their subset world may not be in perfect fidelity to the real thing, but it's an enthralling representation.

Over the next three months, until the Biennial's close on January 3rd, we hope to explore some of its most interesting installations in greater detail. As an introduction, however, we're going to give you a photo portrait of our first impressions being one of the first persons to enter the exhibition shortly after its official opening at 9:00 a.m., Saturday, October 3rd.

|

| click images for larger view |

You enter the lobby and confront the Cultural Center's grand stair.

It's a fall start. Resist the temptation to climb it, as you will find the Cultural Center's showpiece Preston Bradley Hall has no exhibits. Not knowing this, I mounted the stair, and I was taken aback to hear celestial voices rising far above me, as if from heaven.

As I made my way back down to the main floor, I heard music again, very dark, very seductive music, and began walking down the Michigan Avenue galleries to find it.

To my left, I encountered the locked doors to Bold: Alternative Scenarios for Chicago, a sub-exhibition curated by Iker Gill. Blair didn't think much of it, but I found the entries, in turn, maddening, challenging, fascinating, and engaging. I'll be writing more about it later. The thing to know right off, however, is that part of the genius of Herda and Grima is how the Biennial gives lesser known architects their time in sun at the expense of big name firms that often dominate such exhibitions. In fact, it's only in Bold that you'll see contributions from such mainstays as SOM, Krueck and Sexton, and Jahn.

Finally I found the source of the music. Mass Studies+Hyun-Suk Seo from Korea is presenting a video, Zoom Out/Zone Out of 400 photographs of 39 built projects set to the iconic Bernard Hermann score for Hitchcock's Vertigo, with individual images of patterned details sometimes sent swirling like the rotating graphics of Saul Bass's title sequence.

You may not notice the black curtain along the right wall of this gallery. Find it, and step inside, where you will find a number of cases filled with spiderwebs. Tomás Saraceno invites you to contemplate the incredible constructive intricacies of the webs, "complex geometries suspended in air, each piece appears as a unique galaxy floating within an expansive infinite landscape."

From here, make your way back to the beginning, to the Randolph Street entrance, where you can rest in the foyer on the reused materials of Studio Albori's Makeshift . . .

To your left is the Biennial Bookstore, which has a generous selection of books and periodicals. (I picked up a copy of Hilberseimer's recently translated Metropolis-architecture that I didn't know existed.) Here you can pick up Biennial T-shirts, pencils and erasers. Most importantly, make sure you pick up a copy of the official Guidebook - nearly 180 lavishly illustrated pages - so fresh I could still smell the ink. An essential resource and an irresistible bargain at $8.95.

Sharing the space is RAAF's The End of Sitting - Cut Out, a sculpted alternative to the traditional seated desk (you do know standing is a much healthier way to work, right?

Returning to the foyer, you move into Randolph, Pedro and Juana's complete re-design of the Cultural Center's Randolph Square space, complete with adjustable pulleys, new lighting and stylish seating.

On either side under the stairs, an appropriate location for a crime-oriented presentation, is Studio Gang's Polis . . .

. . . showcasing the firm's usual exhaustive research in service for a highly creative reconception of the architectural presence of police in neighborhoods often beset with virulent gun violence. We hope to be writing more about this as well.

Be prepared to encounter the occasional bridal party. They are not an official Biennial exhibit, but a product of the Cultural Center's popularity as a wedding venue.

At the first landing of the stair, you encounter Atelier Bow-Wow's Piranesi Circus, in the sealed terrarium named the Gertrude Bernstein Memorial Garden. An intersecting assemblage of ramps, stairs, ladders, platforms and even a swing "not accessible to the general public but are rather for the use of circus performers - or for imaginary prisoners."

Again, Blair was underwhelmed by the "limp finished design", but in fact the Circus may be the visual linchpin of the entire exhibition.

Viewable at several different levels, the Circus both gives views into individual galleries and reflects their content, creating a complexity of different planes viewable at the same instant.

The constructed window wall of the second-level walkway provides an extra level of complication.

As Tigerman mentioned, the exhibit installations within the Cultural Center has turned one to be of the Biennial's greateststrengths. Designed by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge and completed in 1897 at a cost of $2 million as Chicago's central Public Library, the building's restored interiors are an almost overwhelming collection of grand spaces arrayed in luxury materials, richly ornamented, that includes Tiffany mosaics throughout. They provide a brawny counterpoint to the spare, modernist character of the Biennial installations.

The G.A.R Hall along the north end of the 2nd floor was originally built as a museum and meeting space for the Grand Army of the Republic - Civic War veterans who were still very much a living presence at the time of the library's opening. This may be the first time the hall has seemed almost stretched to capacity, with large scale installations such as Onishimaki+Hyakudayuki Architect's Children's Town . . .

The giant hanging tubes, looking like long fluorescent bulbs of Maio's Floating: The Presence of the Present, Selegascano+Helloeverything's Casa A . .

.

Always in the background are the views out the Cultural Center's tall windows, towards such visual landmarks as Frank Gehry's Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park . . .

. . . the post-fire buildings on Randolph . . .

. . . and the stark Stone Container Building . . .

. . . competing in its abstracted whiteness with Bureau Spectacular/Jimenez Lai's Furniture Urbanism . . .

The exhibition continues into the nearby Chicago Rooms . . .

. . . where Pedro Reyes' People's United Nations: pUN was one of a number of exhibits undergoing its final fine-tuning.

Moving to the fourth floor, we find a way of turning a corner quite different from Mies's . . ..

. . . and in the massive bordello-red walled Yates Gallery, mock-ups of entire houses, with Tatiana Bilbao's Sustainable Housing, a 463 square-foot house that can be built for $8,000 on one end . . .

. . . and MOS Architects Corridor House, built of modules that "approximate the dimensions of a standard corridors and of a sheet of plywood measure 5 x 10", on the other . . .

. . . between them a work at a mannerist inversion of scale, the miniatures of Sou Fujimoto Architects' Architecture is Everywhere, a sea of isolated stick pedestals holding everyday objects suggesting architectural structures . . .

In the hallway leading back to the foyer is Amanda Williams Color(ed) Theory, photos documenting Williams's exploration of the symbolism and power of color in repainting abandoned houses, often standing alone in abandoned landscapes throughout the city.

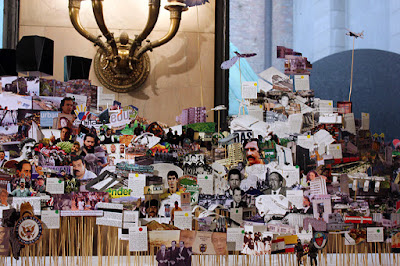

In the foyer, you'll encounter Fake Industries Architectural Agonism + UTS Indo-Pacific Atlas, a collage of 4,000 "that chart the intersections of media, capital flows, gentrification, and post-traumatic conditions . . . "

Underneath the top of the elegant soaring stair, in the land of the heavenly voices, you'll find Al Borde's House under Construction, which is just as the name describes. If you want, you're supposed to be able to follow the progress on the firm's website.

So, some first impressions. A small fraction of what there is to see and consider. We hope you'll follow our subsequent posts, as we continue our profound contemplation both of what's inside the Cultural Center, and at the various remote sites that are also part of the Biennial. Still better, you should check it out for yourself. It's quite a trip.

No comments:

Post a Comment